Column: Is the recession finally coming? Huge data challenges create confusion among investors

Macroeconomic data is vital to society, financial markets, and investors as it gives us a way to measure what the economy is doing and where it is heading.

This is important for company, government, and central bank planning and paramount for asset prices. If macroeconomic data suggests that inflation is low and growth decent, then central banks will be relaxed, and investors will be more keen to invest in risky assets, while the opposite is true if inflation is high and growth weak.

Historically, macro data has often given conflicting signals about the direction of the economy, but there has been more confusion over the past few years than the past few decades.

This has created problems not only for economists and analysts but also for central banks and many investors and their tactical asset allocation (TAA) models.

The problems relate primarily, but not exclusively, to data for the US economy, the world’s biggest and most important for financial markets, but also to European and Chinese data.

Some examples from recent years illuminate the data issue:

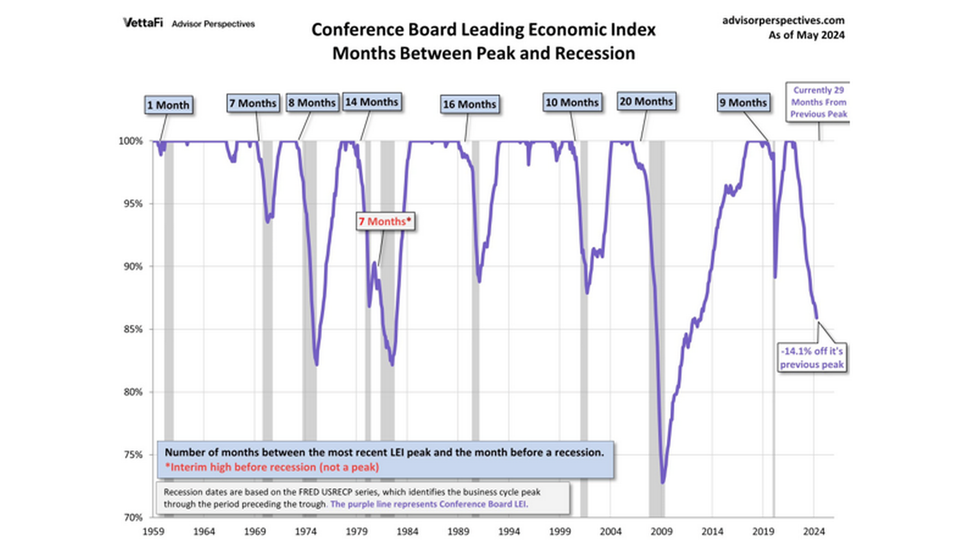

- The Conference Board US Leading Economic Indicator, which has been an important and reliable indicator of turning points for the US economy for decades and is composed of three financial and seven non-financial sub-components, has dropped 14% since it peaked 29 months ago. Since WW2, such a drop has always coincided with a recession, but there is no recession yet in the US, according to the latest GDP data.

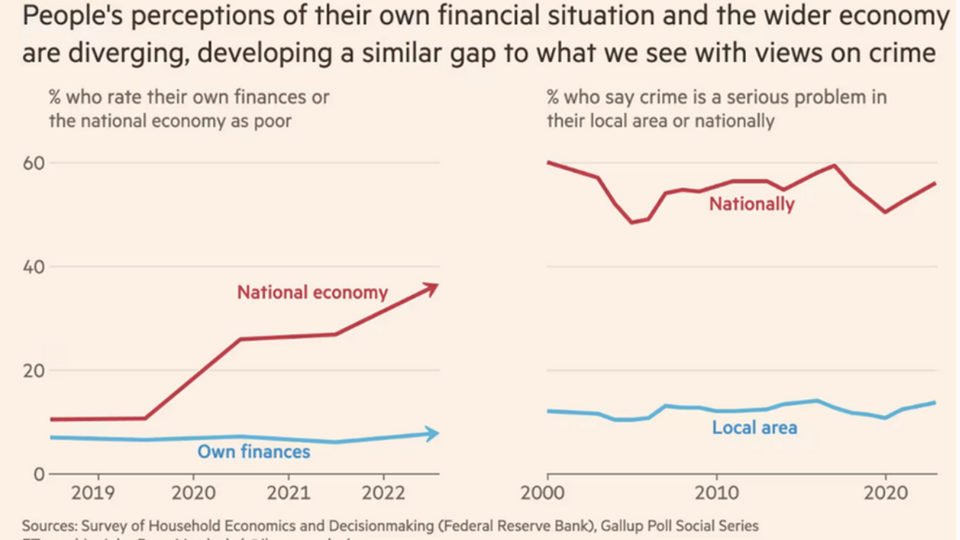

- In several countries, including the US and, to some extent, the Nordics, there has been or remains a wide gap between the consumer sentiment regarding own economy (OK) and the economy in general (not OK) or between the present situation (OK) and the future economic outlook (not OK).

- Banks in the US and Europe have long been raising lending standards according to the quarterly senior loan officer surveys, which historically has always coincided with a rise in default rates, but not this time.

- Surveys covering the same area of the economy but published by different sources show different trends.

- The monthly US jobs reports show remarkably different trajectories, with one showing robust monthly job growth, although significantly lower than initially reported (200K fewer jobs per month), and the other a stagnating employment situation that has lasted for several quarters.

- Several experts believe that growth in the Chinese economy is far weaker than official data suggests, with growth closer to 0-3% versus the official 5.3% for Q1 2024.

Other statistics have also been prone to big revisions, erratic monthly movements or developments that are very different to those provided by other data sources.

There seem to be several explanations for the unusually high level of data uncertainty and why the economic weaknesses suggested by some data haven’t been followed by an economic downturn and higher default rates:

- Corona-effect: Some economists believe historical correlations will prevail, but that the lag from some leading indicators to the economy has been extended in this business cycle not least due to extra savings accumulated and households and companies having obtained cheap loans during the lockdown. The lockdown years maybe also have interfered with seasonal adjustment factors.

- Weaker response: The response rate on several statistics has fallen significantly in many countries, from 70-80% to 35-50%. That is making data more prone to big revisions, prompting erratic moves month to month

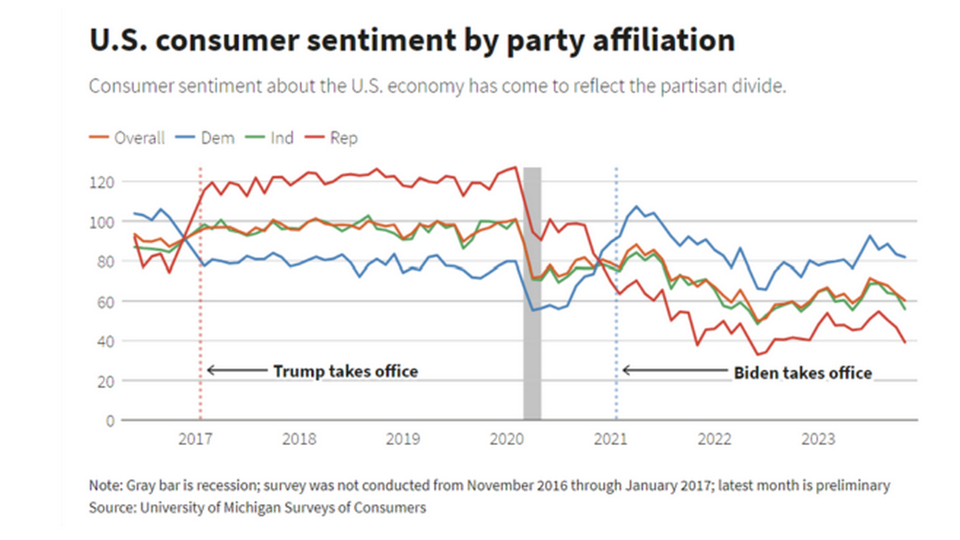

- Partisanship: Increased political partisanship, not least in the US, clearly impacts responses to consumer and business surveys. Republican respondents are more optimistic during a republican presidency and vice versa with Democrats.

- The attention economy is negatively distorting our economic reality: Research conducted by Ben Harris and Aaron Sojourner has found that the competition for views and the optimization of engagement in today’s attention economy means we hear more about bad than good news, creating a negative bias in survey responses.

- Shadow banking: The meteoric rise of private credit can have diminished the signal strength from bank lending data.

- Political interference with data: This is mainly a Chinese issue and has been for many years.

(The column continues below these three graphs. Refresh if graphs don’t show)

More surprises, recession can’t be ruled out

Of course, the above examples lead to great confusion about the true state of the economy, not least in the US, but uncertainty is also high regarding the true state of the Chinese economy, the world’s biggest growth engine.

An analysis by the news media Bloomberg reveals that economists’ forecasts of the monthly US job numbers have fallen from 81% precision in the period 1998-2020 to just 33% post-corona. This clearly suggests that the lockdown period has distorted the data or that some other factor is currently influencing the published numbers with a strong upward bias. It increases the risk of big volatility around important macro data releases.

Downward revised data has recently raised questions about the strength of the US economy, with significant implications, not least for bond yields. Credit and stock markets have so far taken the data in their stride. Volatility and spreads are low, and prices are record high as most investors believe in the soft landing narrative.

However, the weaker data and big downward revisions to previous data have led some prominent economists, and not just some perma-bears, to once again forecast a recession in the US very soon. That would come as a total surprise and does not correspond with signs of healthy consumer demand in both the US and Europe for big discretionary items like vacations and traveling.

The data confusion creates problems for many tactical asset allocation models. Historic correlations between pieces of macro data and yields, credit spreads and sectors have, in several instances, broken down.

The current problems suggest investors should look at datasets that are broader than ever to get a feel for the economy, listen closely to company statements, be even more careful about big tactical bets than usual, and remain very diversified to hedge the risk of sudden surprises in the macroeconomic narratives.

Frank Hvid Petersen has worked in the financial sector and with investments for 30 years as a trained economist, equity strategist, portfolio manager and head of asset allocation at companies like Alfred Berg, Nordea, Carnegie and Jentzen & Partners. He’s the founder of Earlybird Research & Education and writes a weekly free newsletter on macro, investments and megatrends, which can be found at frankhvid.dk.